✰ ★ ✰

scroll for essay

✰ ★ ✰ scroll for essay

images courtesy of Warwick Gow and Jacob Van Der Ley

I met Seamus in the summer. I could barely see them. We were both wearing masks in the wake of that thing that held us captive for two years. I hope ‘[their] skin felt warm and tight, exactly the way [they] like it,’ because mine did not. [1]

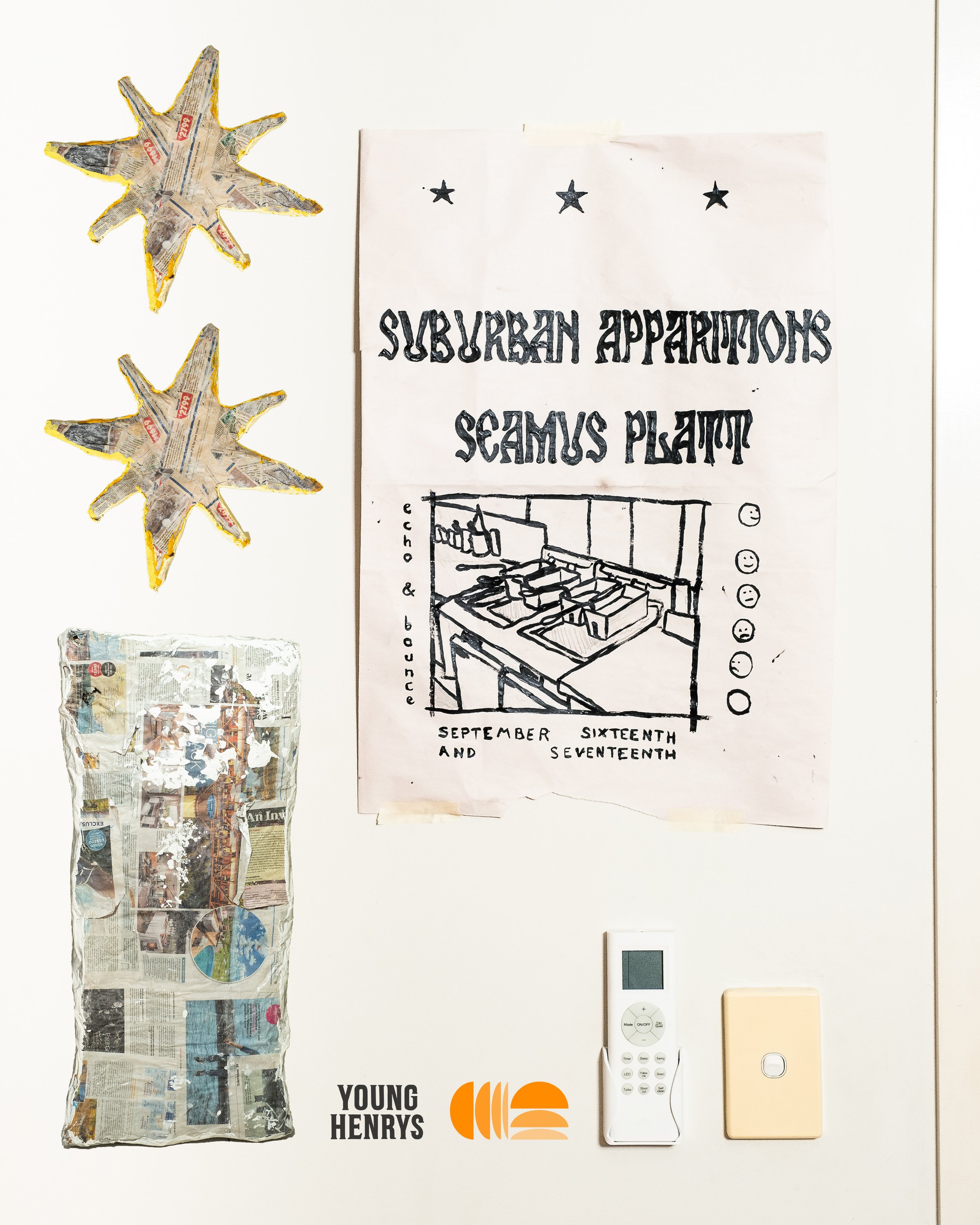

I met Seamus again in the winter. I knocked on a share house door and was taken to their bedroom where I had no trouble seeing all of them: the bed that Seamus sleeps in, the clothes they wear, the books they read, the work upon work that grew out of one corner, slowly taking over sleep space and impatiently mumbling of the practical need for Suburban Apparitions. I understand that this sounds intimate, and I guess it was in a way.

Seamus laid their work out on the bed, one by one. They (the artist and their work) handled each other like brothers and sisters – loving but rough, competitive, each wanting more than the other – wanting the line between the corner that grows and the bed that sleeps to be less of an issue between the two of them. And then, of course, knowing that they are one in the same, cut from the same Alsco tea towel.

Seamus asks me if I would like to take a closer look. I reach for Vigil. It is not my brother or my sister, so I treat it like a newborn.

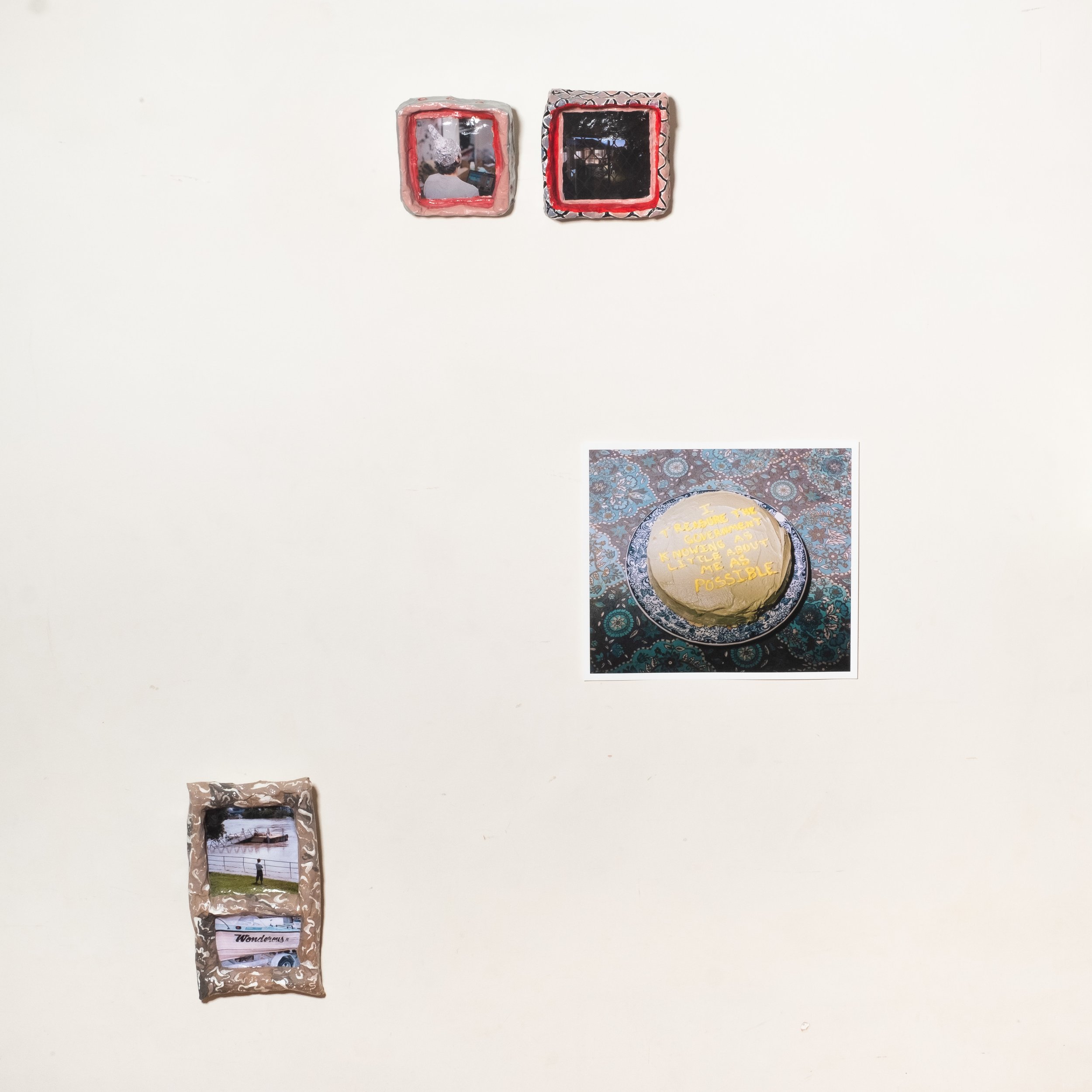

The frame feels light, hollow, glossy, slightly dented. I turn it over to find shadows of the chicken wire beneath the flour, water, vinegar and pulp mâché. I brush and then blow at the dust because here lies a candle and I am a child. Each work is a new vibrant colour featuring paste-ups of medium format, iPhone and digital imagery. The empty vessels tie themselves to The Matrix, MacDonalds, the communal share house bong, and the hospital urine bottle. These are nostalgic references that grow older as they ascend in order, but none feel healthy.

The body of work that has become Suburban Apparitions imitates decorative articles of the home we grew up in: the frame, the vase, the trophy. These vessels were conceived to hold small beloveds: the frame to protect the photograph, the vase to preserve and give posture to the flowers, the trophy to immortalise the under 7s rugby victory and all the things they told us would make us men.

Each imitation is reimagined as though an animation – a picture hanging on the wall of the set of a children’s television show. But the photographs framed by the vessels are not for children with grandiose dreams. They are for people finally realising – at the middle of twenty or the early of thirty – that life regresses to the mean.

Seamus’ photographs are of things that could have been better, more real, less sad – but are familiar and good and sweet and sufficient in their insufficiency. Their photographs are of matters that generally cause worry. I do not enjoy spiders or birthdays (anymore), public toilets, used hairnets, graffiti, stumps of trees or open-heart surgery. I do not like looking back through rearview mirrors nor sharing a bed with someone who would prefer their phone. I am not particularly fond of the washing up, birds, Virgin Mary memorabilia, Toowong Village and its ever-broken escalators.

The sculptures that hold these photographs deceive the narratives they carry for good reason.

Here I understand, because it took me this long, that Seamus speaks in image binding pages from their photobook, Max Pinker’s inspired days in the sun. Both diptych and triptych are effective in their narrative leap, where ‘part of reading fiction is forgetting that you’re doing it.’ I have gone this long believing that the man with the broken heart, the park with one last request, and the dog without a bone are cut from that same Alsco tea towel. And even though they are not, the strength in leap and bind ‘is unreal, and yet it exists in the world to reveal something about it.’[2]

Suburban Apparitions betrays the vessel’s purpose to preserve what it carries; making parody and pastiche of archival quality and rather majorly, the authenticity of documentary photography. I see in them the collage of Carmen Winant’s Hand Studies and Poetry for World Buildings, and the papier-mâché foundations of Franz West, but they sing their own song.

Being a romantic and all, I do think it more important – the way these works sigh at the sight of another candle on the cake. They comprehend our feelings of inadequacy. Instead of appraising the trajectory of our lives with furrowed brow, they choose to applaud and make jest of the hour, the minute, the second – the apparition. They speak words that are refreshingly unlike those of our parents and grandparents. The words that ‘stuck to my back as they passed the mole you thought was malign.’[3]

Words by Alexandra Baxter

[1] From Magnificent Sun, by Seamus Platt.

[2] From an explanation on sequencing by Tate Shaw, director of the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, New York – found in Stefan Vanthuyne’s Fiction as a Visual Strategy in the Photobook: How Contemporary Photographers Challenge the Documentary Genre through the Printed Page within Nele Wynatt’s When Fact is Fiction: Documentary Art in the Post-Truth Era.

[3] From Magnificent Sun, by Seamus Platt.